Although induced demand is not a helpful concept (see my last post), and roads are useful way of generating agglomeration benefits, roads (and private cars) have two big costs. One is the externalities they cause. Another is the land they use. These have important implications.

As I said before, roads satisfy a latent demand for journeys, make housing cheaper by opening up much more land for productive development, support economic agglomeration, and helped start the Industrial Revolution. It’s a mistake to try and come up with motivated reasoning to argue that roads have no upsides at all.

The lesson we should take from this is not, however, that roads are always the best transport mode, that historical schemes to bulldoze our cities for them were good ideas, and that we should push against every scheme for pedestrianisation and reducing traffic in city centres.

The first issue is that cars take up a lot of space relative to the person they are transporting. Online urbanists have pointed this out so many times that you might think it's a canard, but it is important. Including stopping distances, cars take up the space of 20 people.

This means that if lots of people want to do exactly the same trip, then despite the fact cars have engines and can go pretty fast, they're often slower at moving lots of people than just walking, as you have to squeeze so much extra material through the available space.

For example, all of New York City’s bridges carried more people per day when they were devoted to transit and pedestrians, usually about 100 years ago, than they do now when all or nearly all the spaces has been given over to cars. The Brooklyn Bridge had 426,000 crossings at its peak time vs 178,000 now.

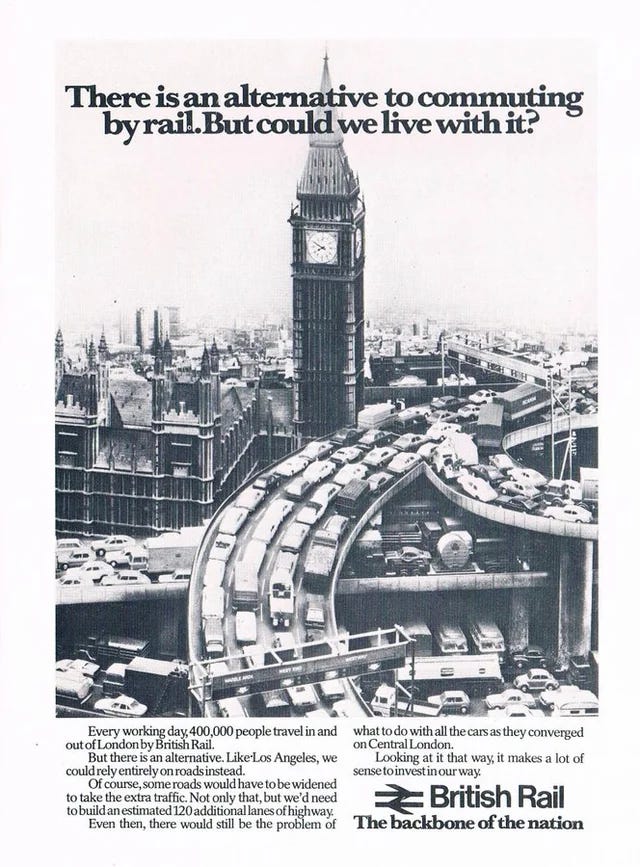

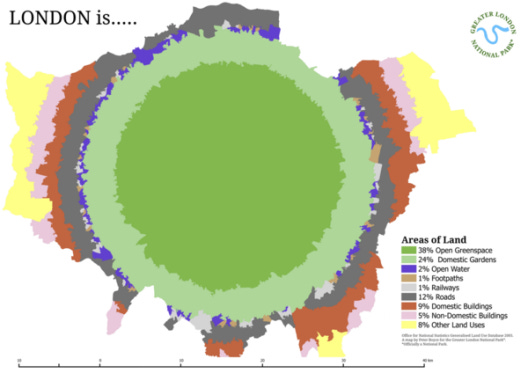

Or for another example, London has over 2m railway journeys per day and 5m tube journeys on the 1% of its land that is railways and stations. And there are still some lines with spare capacity if the trains could be found to run. By contrast there are about 6m trips per day (including both car passenger and driver) on the 12% of its space that is road – slightly fewer journeys on twelve times more land (though buses and bicycles use the space too).

Setting aside roadspace in the centre of cities at ground level does not just spend it on that use, nor just make the area polluted and noisy, it also prevents other modes of transport. Walking around Manhattan feels endless, because of all the waiting to cross roads.

And this is all much worse if we expect to store cars while parked as well – as opposed to say, having driverless cars or taxicabs that are always carrying passengers around rather than sitting idle, because we use a whole bunch of extra land up for that storage.

Cars have also got much bigger over time as we have got richer (on the demand side) and more efficient/productive at making them (on the supply side). This makes for a much nicer drive, but it worsens the space costs of driving, and these bigger and heavier cars are somewhat more dangerous for everyone who’s not in them.

For roads like motorways, which are mostly in the countryside, this doesn't really matter. Road links between cities are very important, and the alternative use of the land is usually just farming, worth about £10,000 per acre (£25,000 per hectare). We have 16.843 million hectares of farmland in the UK, and it covers 69% of the UK, and while it is very important in total, we can generally spare a few hundred acres of it for a motorway. For much less densely populated countries like France, Spain, or the USA, this goes even more strongly.

Land in cities, by contrast, is very scarce, especially in the centre. Land in Westminster, London's most expensive borough, averages £93 million per hectare – 9,300 times more than farmland – and that's with today's planning constraints. A plot of land in Westminster without any planning constraints would go for quite a lot more. 49 Park Lane went for £3,300 per square foot. At 55 storeys (like the Hilton down the road), 1/2 hectare would have about 1 million square feet of usable space, £3.3 billion worth, and about 300,000 times more than farmland.

So land in the most prime areas can be nearly a million times more valuable than land outside cities. This is of course, why we build upwards when land is scarce, and we build at low density in low value areas, since we have ample cheap land. (The early sections of this recent spatial economics paper from New Zealand explains this economics of land very carefully.)

This is also part of the reason why urban railways have often been shifted underground. (The other part of the reason is the second half of this article: the noise and pollution externalities railways generate, especially steam railways.)

This all suggests we want to direct driving around the centre of cities with bypasses and ring roads. Roads in the centre should mostly be for access. Where possible, arterials should go underground as they approach the centre, just like metros/tubes and utility cables.

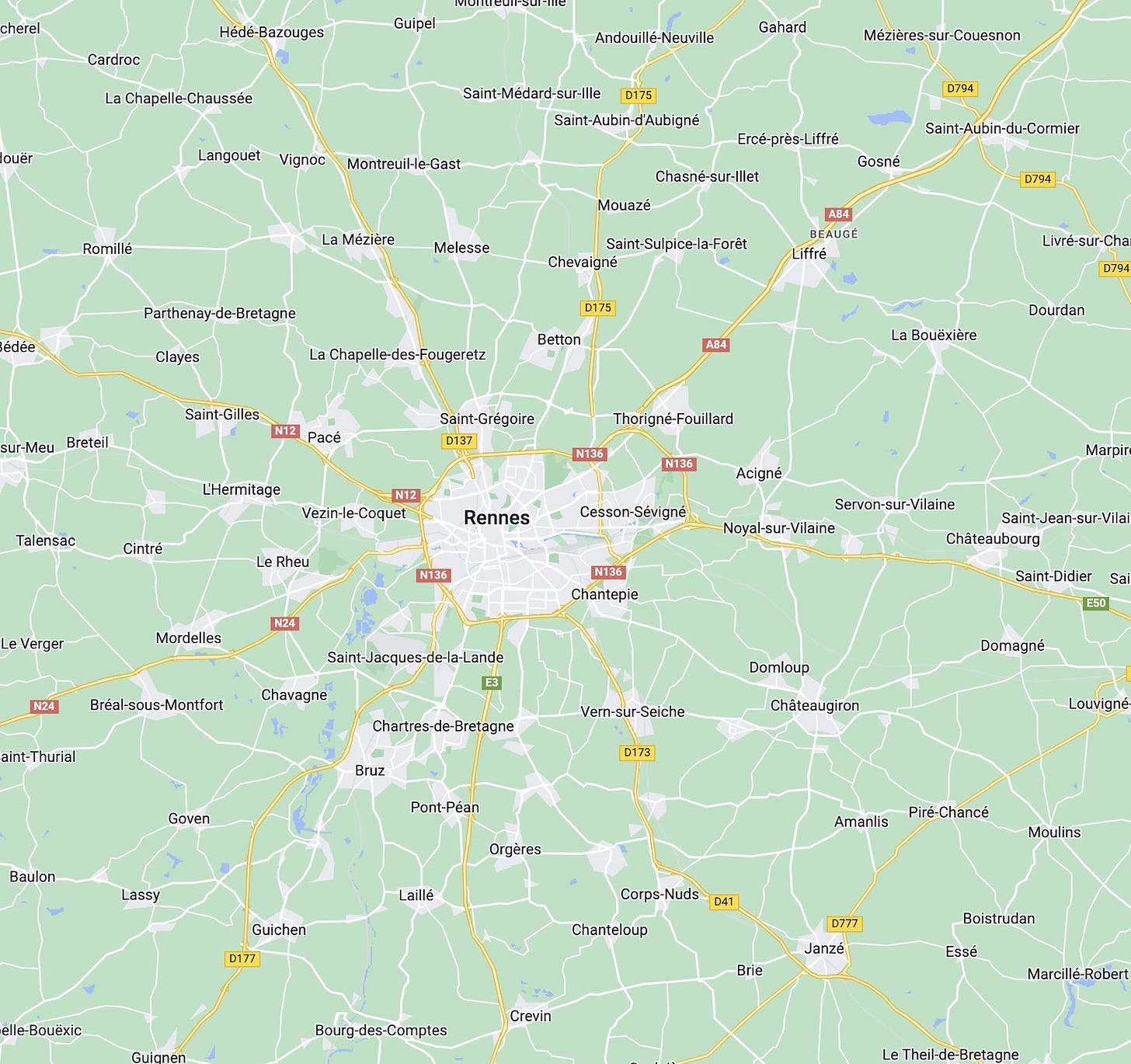

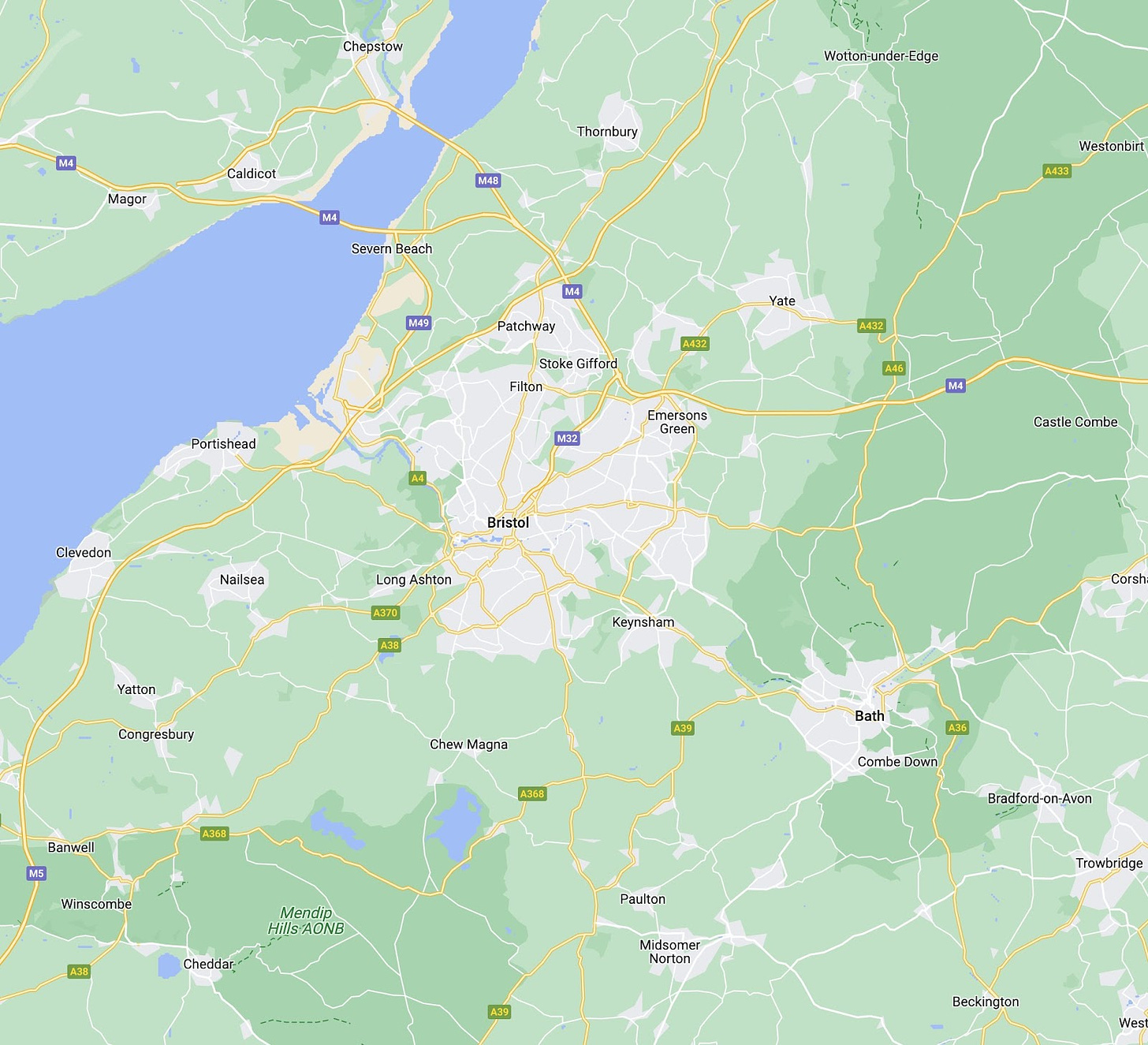

Take Rennes (France) and Bristol (UK), which have core cities and metropolitan areas of roughly the same population. Rennes is neatly ringed, Bristol has major roads driving right through the centre. My story implies the Rennes approach is superior. Rennes actually has more lane-miles of road than Bristol in total, but this is mostly segregated from where people live, work, recreate, and so on.

So the first problem with roads and private car travel is that they are extremely space inefficient, meaning that they are inappropriate in the centre of cities.

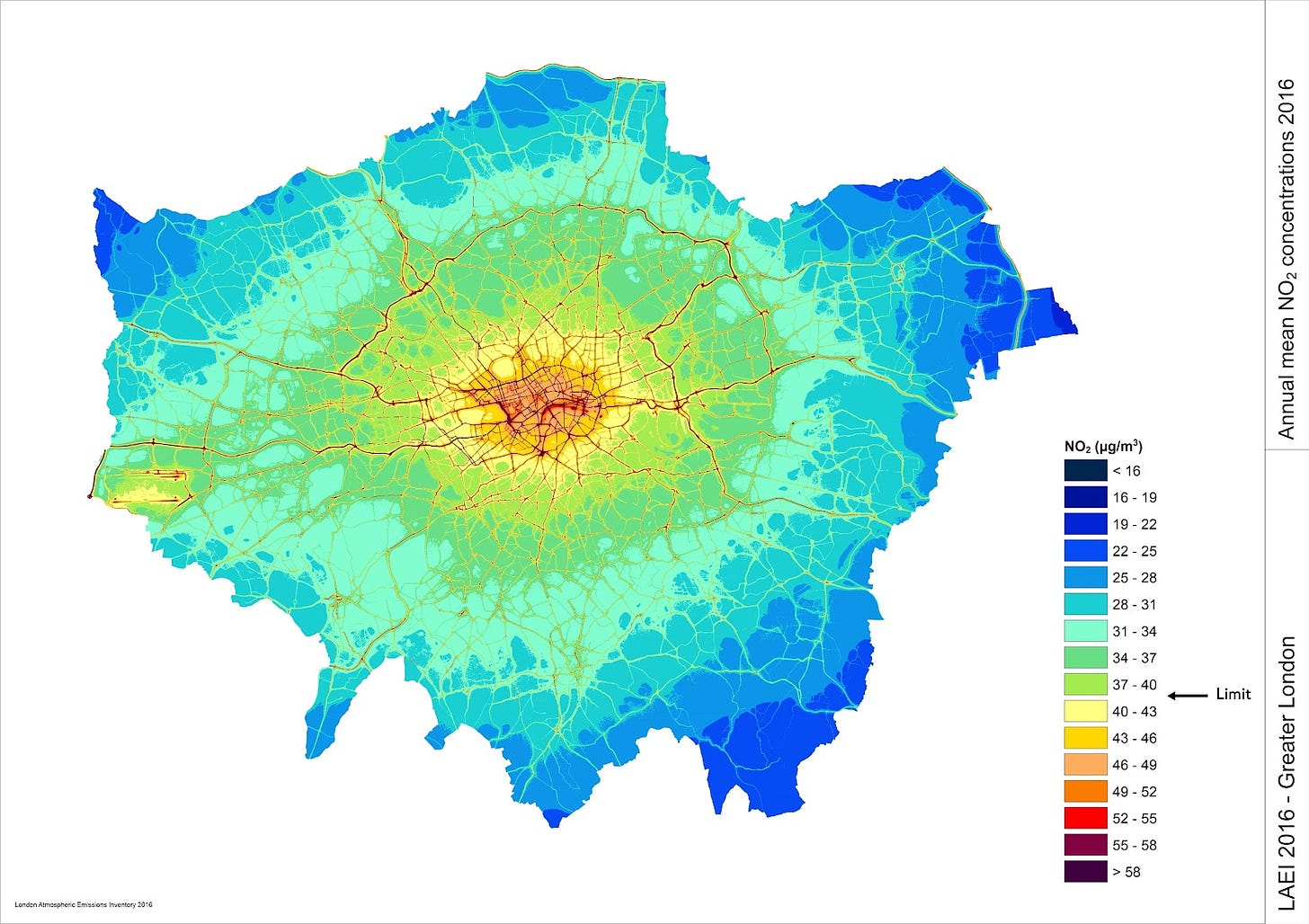

Notice anything about this fine-grained map of Nitrogen Dioxide pollution? Things get worse as you get to the centre, but above all, pollution is driven by roads. The same is true for PM2.5s and other air pollutants. Air pollution is really bad for brain development, lung health, and more. And road use is the number one cause of air pollution in the UK (as in most other developed countries) – which everyone knows intuitively from tasting and smelling the air near roads.

Hopefully, electric vehicles make a big difference to solving it; tyres and brakes mean they will not completely eliminate pollution but I gather they will roughly half it. Sadly, however, they will make very little difference to solving noise pollution, as EVs make a very similar amount of noise above about 20mph.

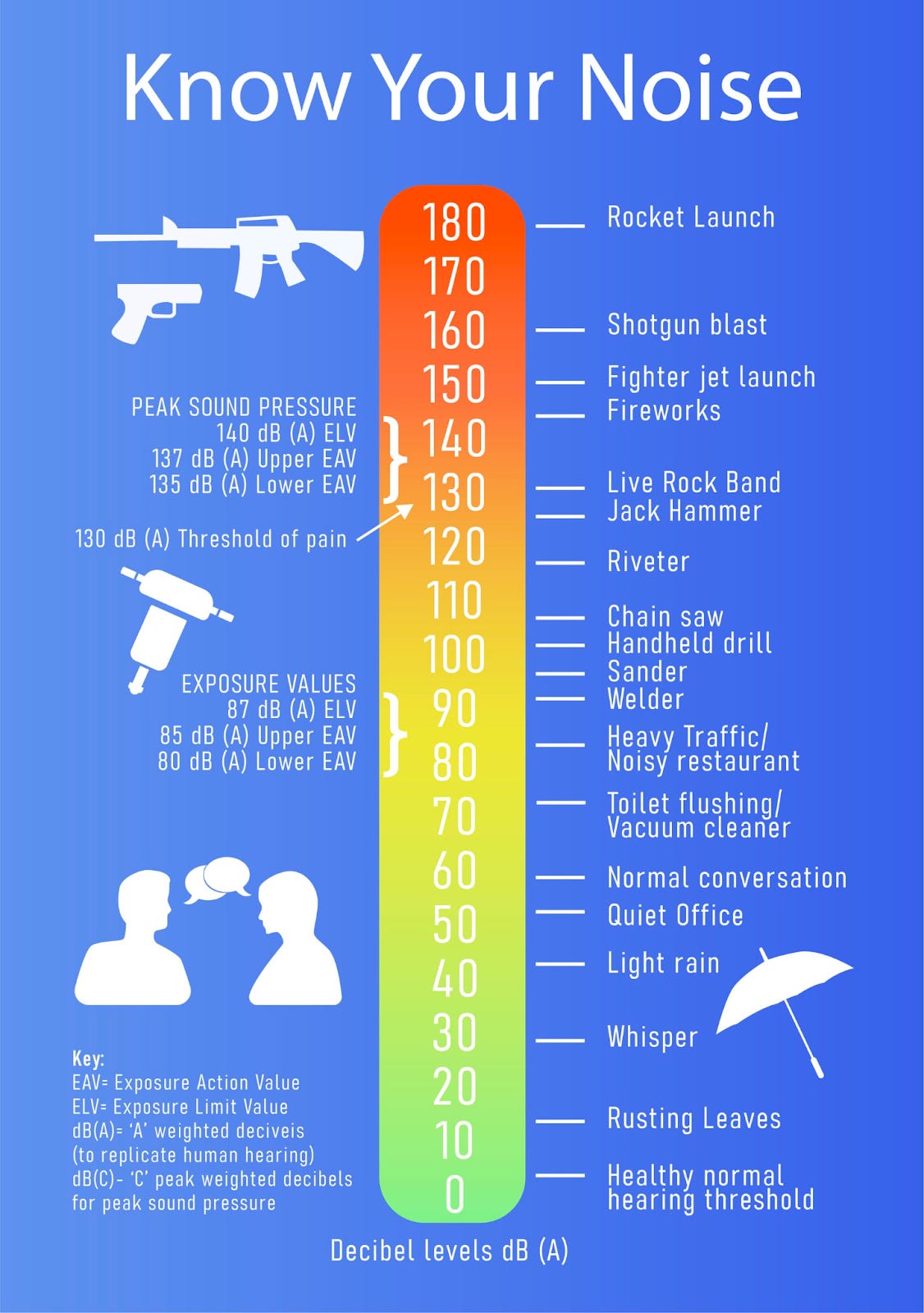

People hate noise, and this is reflected in house prices. One 1976 paper found that house prices got higher the further you were away from a major new road – the I-495 in North Springfield, Virginia – for the first 1,150 feet, as the cost of the noise and air pollution dissipated, but then began to decline as the benefits of access to the network declined.

A more recent Swedish study found that each decibel of extra road noise cut 0.6% from a property’s value – being in the loudest places cut a full 30% off its price. A comparable study for Glasgow, UK found similar, but smaller, results. An ingenious study pairing two million 100 square metre units, and sound measurements there, with 100,000 property sales, in the Netherlands, also found there was a very large impact from noise.

We can back this up with evidence from aeroplane noise too. According to a 2009 study of 66,000 house sales in the Netherlands, each decibel of aeroplane noise a property is regularly exposed to above 45 decibels (roughly the volume of light rain), wipes about €1,900 off the property’s value. Different studies find different exact values, in part due to differences in methodology, data availability, local context, and so on, but results are fairly consistent: some 0.5% to 3% is taken off house prices by each extra decibel.

No one wants to live on a through road – in addition to the noise and the pollution, it’s generally not safe for your children to play around in the street. Apparently, residents on cul-de-sacs tend to lend their neighbours tools more, and are more likely to go over to their neighbours’ for tea.

All this together is why homes on cul-de-sacs tend to sell for a lot more. One study found they were worth 30% more than other similar properties. Thus, if allowed to do so, developers will invariably develop all new neighbourhoods as cul-de-sacs, to prevent people from living with traffic going by their house. Great Estates always blocked through traffic if they could.

All this means that we should consider the massive externalities of roads, as well as the benefits they give us. We have two ways of doing this: first, we can try and make sure most of our important roadspace is not near where most people spend their time; and second we can try and reduce the harms that road use has on those who live by it.

How can we keep traffic away from people? Two major options we’ve gone for in the past are bypasses, which have been built to allow traffic to go past a town or a village so its ancient high street need not be full of whizzing vehicles, and ring roads, like the M25, which are effectively the same thing, but from all directions. (Though not all ring roads are created equal.)

When you have a credible bypass, then even without significant driving restrictions in the centre, you will see most of the traffic just go the quickest, most convenient route on the infrastructure meant for it. This is absolutely clear to me from driving around Spain.

If paired with sensible restrictions on through traffic in the centre of these towns, villages, and cities, ring roads and bypasses can give us a win-win: good driving infrastructure, but with most of the traffic happening relatively far away from people’s houses. In fact, this was the principle behind the 1963 Buchanan Report – Traffic in Towns.

Another option is low traffic neighbourhoods, which restrict through traffic in residential areas to main arterials, to prevent ‘rat running’ through minor streets. Effectively, they turn minor streets into cul-de-sacs for cars, but leave them as through streets for cyclists, pedestrians, and emergency vehicles.

I think LTNs are generally a good thing, because the benefit to the people on the closed streets outweighs the cost to the drivers who have worse commutes from the LTNs on their routes.

But right now, these drivers have a very fair case that they are being disadvantaged by the extra traffic they face. It is always distressing to have the rules of the game changed in a way that disadvantages you. I think the fair way to solve this problem would be to build more and better major roads so that they can get around as well as before – but in a way that allows us to massively improve residential streets. I honestly think that such a win-win approach could make a lot of the LTN controversy go away.

A third way to move traffic away from where people live or hang out is tunnels. We should be tunneling many more roads. The tunneled road could be wider than its surface-level predecessor – happy drivers – and we could even fund the tunneling by building homes on top of the land. And the pollution and noise has been solved. But this is a whole topic of its own, and I intend to write much more about it.

In addition to moving traffic off the streets on which people live, how can we reduce the harm of the roads we do have? The first thing is to try and make traffic less polluting. The best way to do this is just to wait, as electric vehicles continue to improve massively every year, and pollute less than half as much as regular cars. They will hopefully take over. And at 20mph they are nearly silent except for their beautiful metallic safety drone, meaning they will also vastly reduce the nasty noise impact of traffic.

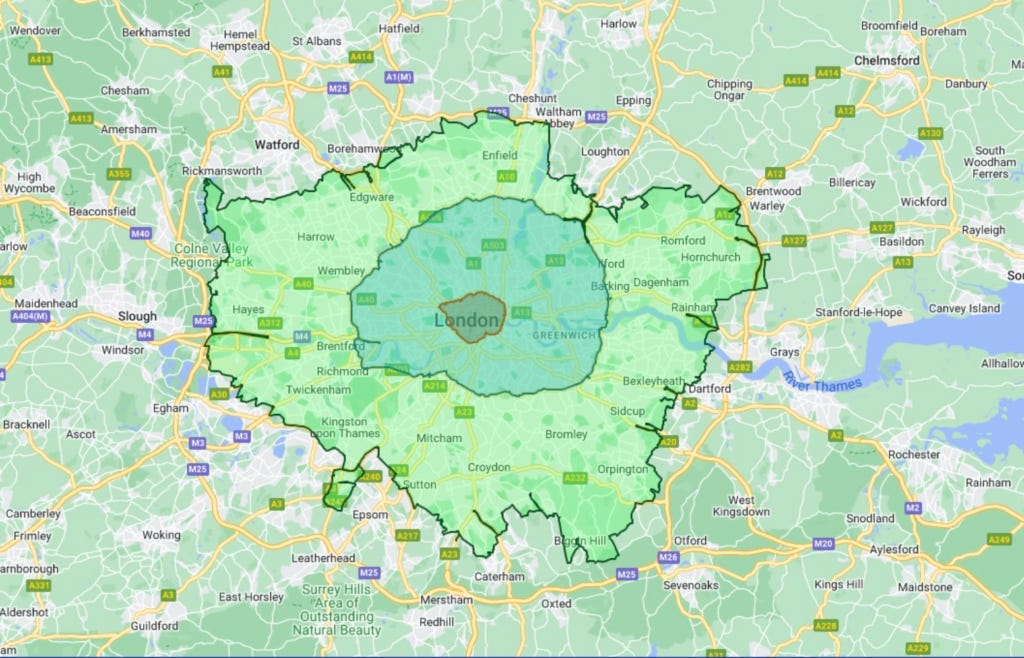

But it will take decades for our ‘fleet’ to completely shift to electric, and my lungs are suffering right now. So one thing we can do that has a more rapid impact is impose restrictions on which cars can come into the centre of cities. This is the principle behind the original ULEZ, and it’s a good one (I say this as someone who lives right on the boundary of the zone before the recent expansion, and who paid a great many fines before I eventually had to buy a new car to meet the standards). I’m not so sure about the massive and controversial recent expansion of the zone (pictured below), as it reaches areas that are not nearly dense inner city, and so the negative impact of emissions and noise there is correspondingly much smaller.

Another thing I recently learned that could make a huge difference, is to put noise barriers on major roads. Apparently this is common outside the UK, especially on viaducts. They are widely used in central Europe, particularly in Poland. California has 760 miles of them and Florida 250.

In the UK, it has been implemented on and off around the strategic road network, e.g. around Luton on the M1 and Cambridge on the A14. Grow some vines to cover them up and they even improve the view. Or put solar panels on top. We could start with the Westway and other major roads that go into cities.

Many sound barriers claim reductions of 15 decibels or more which is approximately the difference between nearby heavy traffic, and the sound of rain, or a normal conversation in the background – which would be night and day near the UK’s major roads.

We should also be enforcing our existing laws against excessive road noise, especially motorbikes with illegal exhausts, ideally with automatic radar cameras as in Paris.

These two facts: that roads are essential infrastructure, but also cause harm to those nearby, suggests there is space for a win-win political compromise. More roads in the right places, fewer cars in the wrong places. More agglomeration, less noise where it matters.

It’s clearly not impossible: the Netherlands uses about 3x as much land as we do, per capita, for roads, but has legendarily quiet and safe neighbourhoods. These two things are just not at odds. I think there could be massive political rewards to politicians who could come up with the deft policies that square this circle.

Great article! I so appreciate your objective, first principles approach here--as against taking a pro- or anti-car general attitude.

You mention the Netherlands at the end. That in my mind raises the question of the role of bicycles. The single most striking thing when visiting that country is the hundreds of bicycles everywhere--the bike parking garages near train stations, the bike pathways that enable safe commutes, and just the presence of bikes everywhere.

I’m in the US, where heat, hills, and spread-out suburbs make biking as transportation less viable. But what about e-bikes? An e-bike is a legitimate single-modal transportation tool for distance up to maybe 15 or so km (10 miles). In many European and US East Coast cities, combined with good bike infrastructure they could take many cars off the streets. Even in a place like LA with its multi-center, car-centric development, 10 miles takes you from many neighborhoods to their local shopping areas, schools, and civic infrastructure. Right now, hardly anyone bikes here (biking is for exercise, not for transport) yet I think e-bikes, if we fully embraced them, could change that. They already are growing popular with young people: my kids’ high school this year installed e-bike parking and I’d guess about 10-15% of kids ride bikes now, reducing the drop-off car traffic jam considerably.

I wrote about e-bikes and some of their potential here: https://open.substack.com/pub/heikelarson/p/e-bikes-cool-tools-with-hot-benefits

I just love how many different people choose e-bikes and wish we’d fine a way to use this new tool to make our cities more like Amsterdam.

Interesting series of essays! I wanted to respond to a point. From what I understand, tunnelling a road is going to be a lot less cost-effective than tunnelling a train every time. A train can do 32000+ people per hour per direction and a road lane can do 2000 pphpd. If the problem is a capacity constraint and the demand is along a line that can be served by a train, a road tunnel is not going to look good on a cost-benefit analysis

This is before considering ventilation requirements for internal combustion cars and trucks