The government needs an infrastructure plan

Building homes without new roads and railways is a recipe for disaster

On Tuesday (16th December) the UK government announced that, subject to a 12-week consultation, it would implement a raft of radical reforms to English planning through the National Planning Policy Framework. If it is delivered, it would be the most transformative reform to the planning system since the introduction of the Town and Country Planning Act and green belts in the late 1940s.

The National Planning Policy Framework is a central document, introduced in 2012, with which all local plans in England are required to be consistent (planning is devolved to Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland). Usually, tweaks to it take several years to be reflected in plans, and while plans are being updated, existing policies remain partly in force.

But housing minister Matthew Pennycook, in his speech, said that local plans should be given ‘very little weight’ where they contradict the new framework, effectively invalidating them. The new framework could come into force in just a few months. This means that, in principle, developers could be submitting successful planning applications in line with the new NPPF in the summer of 2026.

The changes would, among many other things:

Remove the ability of councils to block housing and mixed use development on the grounds that it is in one of England’s green belts within 800 metres of a train station (GB7.1.h), so long as any proposed developed is denser than 50 dwellings per hectare, as well as creating a presumption that such development should be approved unless its benefits would be ‘substantially outweighed’ by adverse effects (S5.1.h).

Introduce a presumption that anyone, anywhere in the country, be allowed to build additional homes in their back garden (L2.1). Strikingly, this need not be a single granny flat, but could be multiple units, or even a small block of flats, so long as its overall footprint (the amount of floor area it uses) is no greater than double the existing property, and so long as it does not use up more than half the undeveloped area of the plot.

Remove the ability of councils to ‘gold plate’ building regulations (PM13), the rules that govern the basic standard of homes that developers are allowed to build. No more could individual councils or mayoralties require stricter rights to light, or balconies, or dual aspect, and so on.

Give very small sites (under a quarter of a hectare) an exemption from the requirement that otherwise exists for all development to prove it generates a net improvement for biodiversity.

There are some serious hurdles that the policy will need to clear during the consultation period. It may leave big loopholes. For example, GB7.h.iv may allow a clever council to prevent any of the new presumptions applying by generating a comprehensive redevelopment plan for the area around a station, even if it rejects any planning applications made to fill out parts of that plan.

It may be held back by other parts of the system. Viability tests appear to have been removed as a constraint on social and affordable housing demands, meaning that all developments pursuant to these changes may all be required to be 35 percent social housing, as well as 15 percent below-market rent (‘affordable’). In many areas, this will make development unviable. Even where it does not push development out of viability, it will use up an enormous fraction of any value generated by granting the permissions.

Even if the Government removes glitches like these after the consultation, there will be political blowback to handle. Britain has seen many rounds of abortive planning reform: in recent decades, there was New Labour’s attempt to allow more suburban densification (subsequently revoked), the Conservatives’ attempt to reform planning rules in the Planning for the Future white paper (largely abandoned), the current government’s attempt to reform environmental restrictions in the Planning Bill (hollowed out), and many others. The Government will need courage, vigour and resourcefulness to win the political battle.

The infrastructure deficit

These are all issues. One other issue which could be huge, though, is infrastructure. Development unlocked by the new rules is likely to be concentrated in the South East, where housing scarcity is greatest and prices highest. YIMBY Alliance estimates that the new rules on development near stations could create space for an estimated one million homes in this region. The rules around garden flats could create many millions more – there are seven million houses with gardens in London and the South East.

With 2.35 people in the average household, this could mean enormous growth in the population of the London metropolitan area – perhaps by millions – over ten years. This vast new population will need a huge amount of new transport infrastructure, a fundamental upgrading of the transport capacity of southeast England.

The NPPF draft makes no real provision for this. Development will be subject to the usual charges.1 These systems are often adequate for funding routine local transport infrastructure like access roads or bus stops. But nobody expects these to fund massive region-wide projects of the kind that will be needed.

This is concerning. There are now more rail passengers into English cities than before Covid. At peak times, most lines entering London are already at capacity: over 100,000 people are forced to stand on the trains into London every morning. In 2019, London was rated by the OECD’s researchers as the major city with the worst roads in the entire developed world, the only place in their entire sample where driving was generally slower than taking public transport. If millions of people are added to the South East they will either be unable to access road and rail, or they will cannibalise the road and rail use of existing residents.

Why we can’t just build first and ask questions later

One might suppose this problem will be easy enough to solve further down the line. If we really did build a million homes in the South East, it would release enormous economic growth, perhaps four percent per year, as we converged towards our pre-2005 growth trend. The Treasury would be replete with cash. One might assume that it could just fund the infrastructure later, as this happens.

Don’t depend on it. The UK government is incredibly bad at responding elastically to shifts in demand around the country. The population of Britain has grown by ten million, and shifted significantly around since 1992, but we have gained no reservoirs in that 33 years. Heathrow actually has fewer runways now than when it was first built, and the number of aircraft movements (takeoffs and landings) has been flat for 24 years. Our motorway programme stalled after 1997, since when France has added as many miles of motorway to their network as Britain has in total.

Since the A13 and the M25, London and the wider South East have seen barely any major roads built, even though there are 50 percent more cars on the roads than 30 years ago, and even though between 1991 and 2021 its population increased by six million, more people than live in Denmark. No wonder that the region has the most congested roads in the country. Nationwide, the number of railway services increased by 32 percent between 1998 and 2019, while passenger numbers doubled.

Successful infrastructure projects can take an incredibly long time to get off the ground, even when the government isn’t hard up. The Elizabeth Line was first proposed in a report in 1974. It received government backing in the late 1980s but was cancelled in 1994. Planning restarted in 2001, it was approved in 2008, and it finally opened late in 2022. Outside London, cities are left waiting even longer.

Many British projects are also very expensive: HS2 is the most expensive new railway in the world, costing 5.5 times as much per kilometre as the next-most-expensive high-speed line, which is being built between Lyon and Turin and includes a tunnel under Mont Blanc. This makes the taxpayer, and its representative, HM Treasury, reluctant to fund more infrastructure, which is part of why it takes so long to build.

If this infrastructure doesn’t arrive, it will create two big problems. First, the public will be more likely to revolt against the increase in building, because it is making their lives worse as they sit in more traffic and can’t get a seat on the train. Some NIMBY grievances may be pretextual or frivolous, but overloaded transport infrastructure is a completely real way in which development makes the lives of existing residents worse.

Second, it will undermine the benefits of new housing itself. The main purpose of adding more homes to successful urban agglomerations is to allow people to move towards better paid jobs from lower-productivity areas. But if congestion on trains and cars worsens sufficiently – and 2.3 million people would do that – then the incomers will be improving their own lot at the expense of the existing residents. Slower transport means smaller job markets and lower productivity.

Too many people and not enough roads is a big part of why developing countries are poor. A World Bank report found that traffic congestion in Cairo makes Egypt about four percent poorer, roughly equivalent to the contraction in the UK economy after the Financial Crisis. We do not want the London metropolitan area to become a ‘Cairo of the North’.

Crossrails

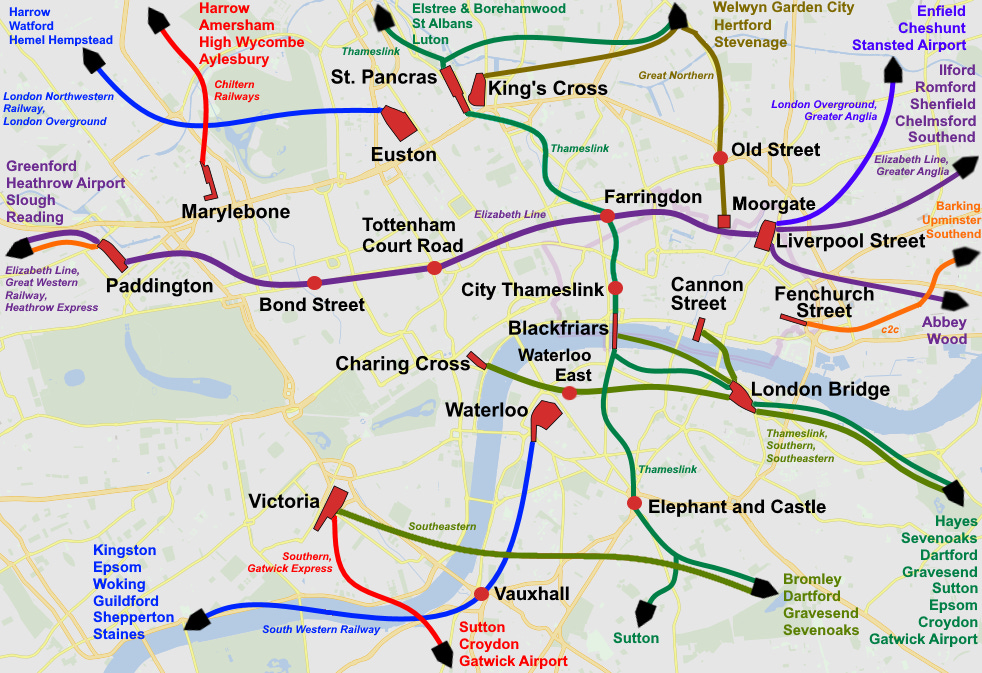

Luckily, there is a surprisingly easy solution to rail overcrowding in London: crossrails. Most of Britain’s railways were built in the 1840s and 50s, at which time it was almost impossible to tunnel a railway under a city centre. As a result, London’s railways generally terminate at a big station on the edge of the centre, like Waterloo or Victoria.

This was the best the Victorians could do with the technology available to them, but it imposes a low ceiling on capacity. Terminating a train takes far longer than stopping and carrying on, especially in the centre, where most passengers are going. Many more platforms are thus required at a terminus station than there are pairs of lines going in if platform capacity is not to become the binding constraint on the capacity of the entire network. For example, Waterloo has four pairs of lines going in, which could carry perhaps 96 trains per hour, but only 24 platforms, which turn around no more than 42 trains per hour. Terminus capacity at Waterloo thus halves the total capacity of the enormous rail network that fans out from it, compromising the transport system of the whole of southwest London and much of southern England.

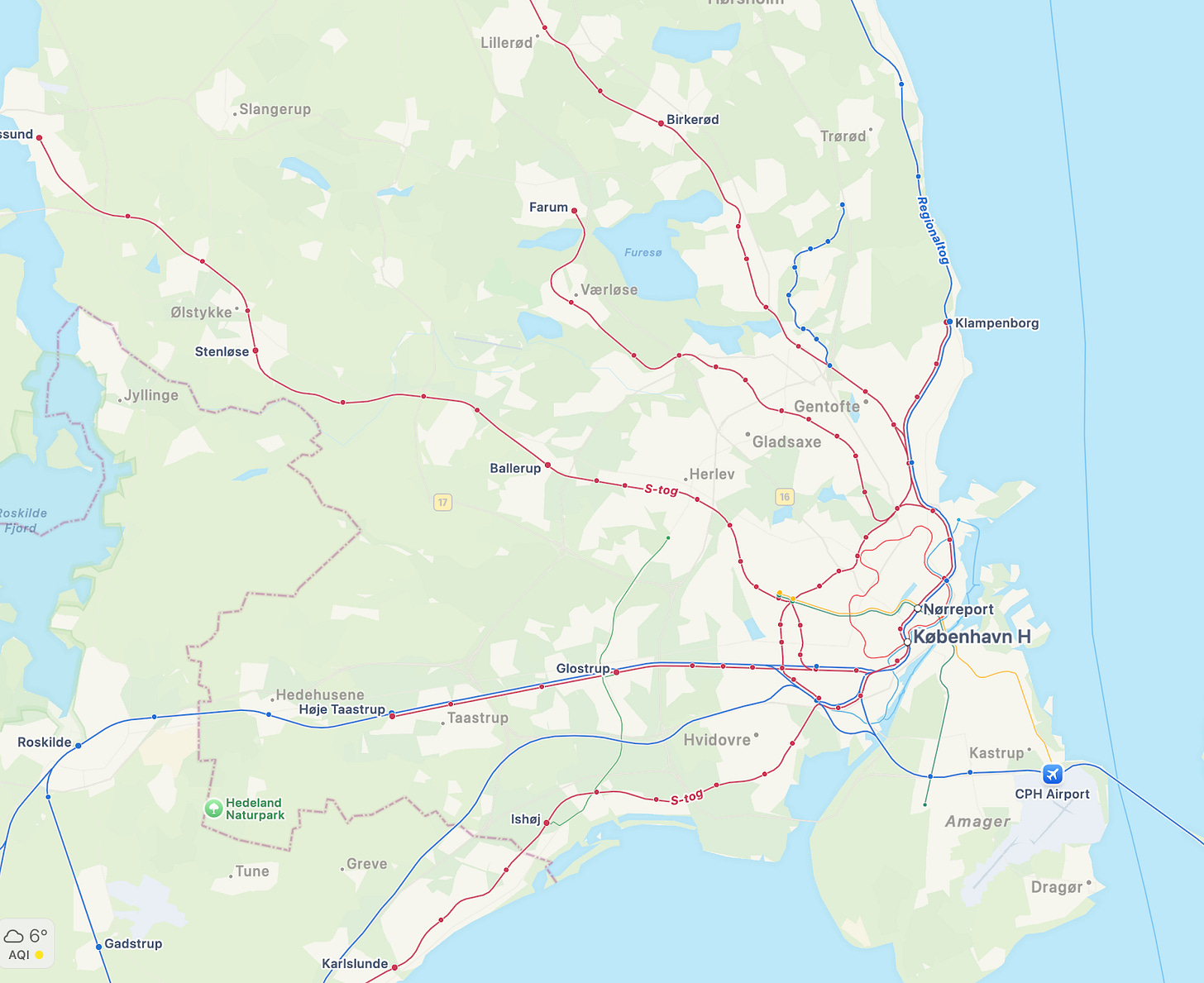

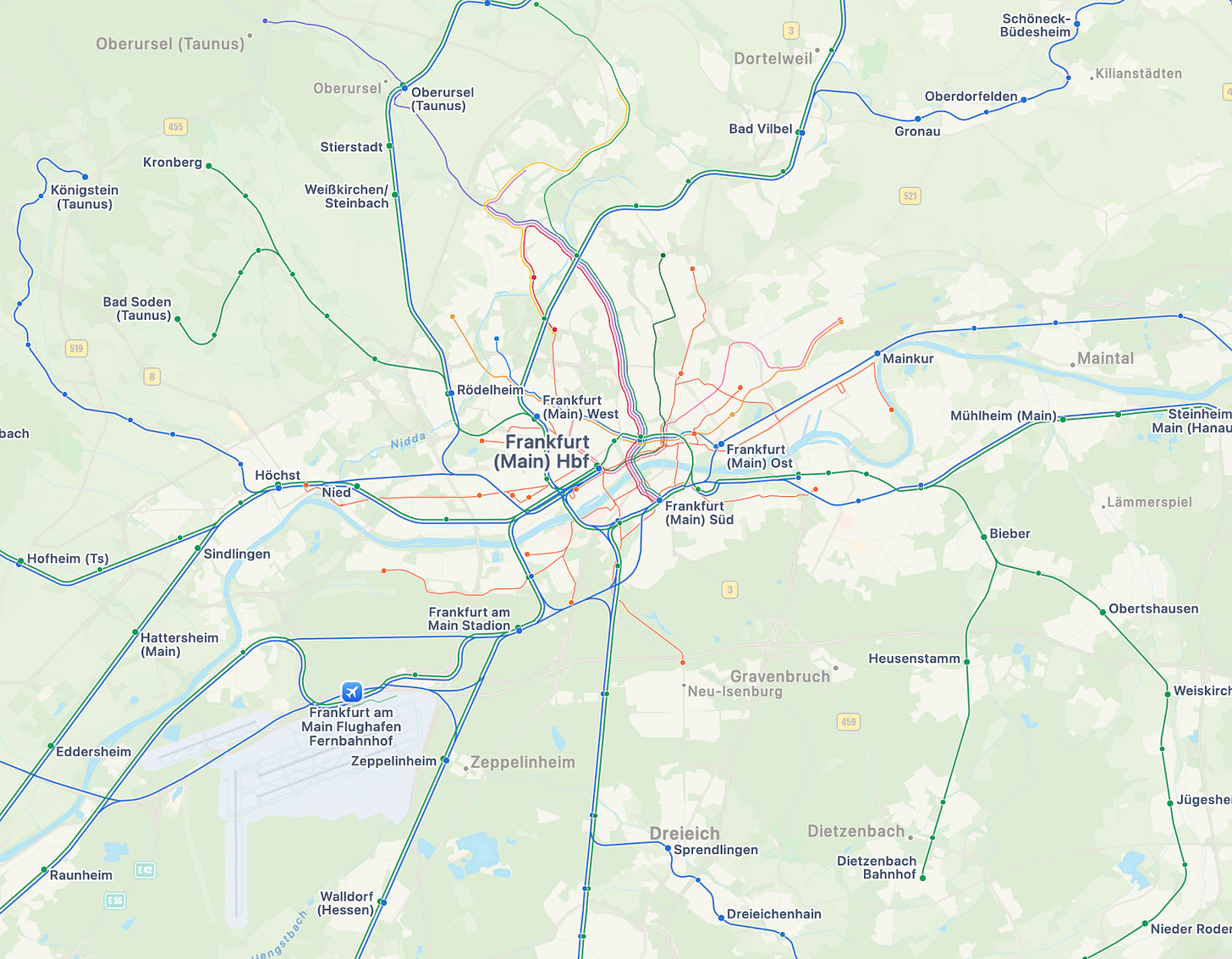

The solution is joining up two terminating networks, each on opposite sides of the city centre with a tunnel (or occasionally a viaduct). The old suburban railway systems of Paris, Madrid, Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Zurich, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Vienna, Copenhagen, Oslo and Stockholm have all been joined up, creating immensely powerful networks like the Paris RER, the Madrid Cercanías, and the German S-Bahns. Crossrailing has also been practised on a huge scale in Japan, with Tokyo joining up no fewer than thirty lines between the 1960s and the 2010s.

Urban expansion in postwar Europe has been fundamentally shaped by it too, with much development concentrated around railway stations on the joined-up nineteenth-century lines. In effect, crossrailing has systematically enabled the kind of rail-orientated development the Government is proposing for decades in countries like Spain, Germany and Denmark.

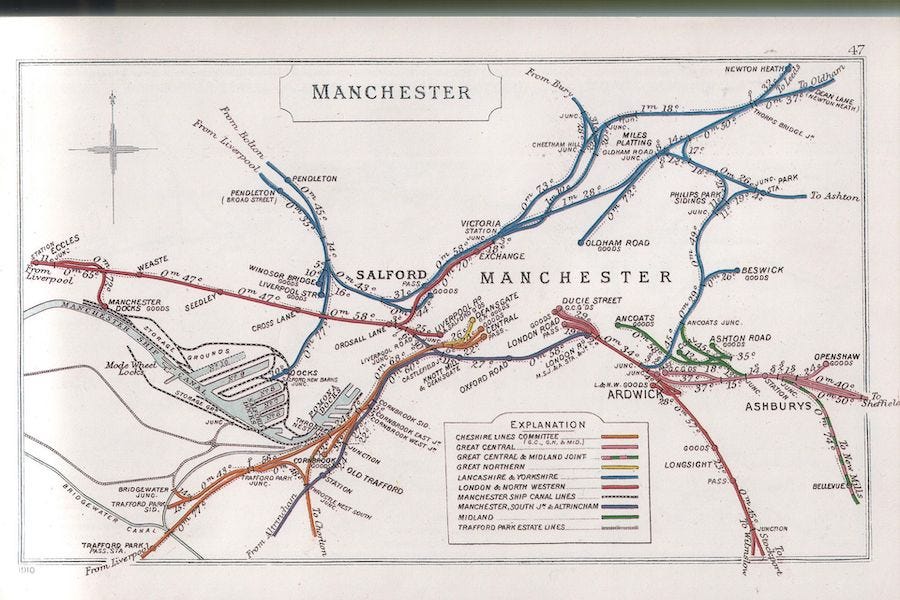

Crossrailing is not unknown in British history either. London completed one of the world’s first crossrail projects with the Snow Hill Tunnel, creating what became Thameslink in the 1980s. The Central Line extension was another example in the 1930s. Liverpool did this twice in the 1970s, and Newcastle once. Much of the Manchester Metrolink operates on a similar principle, weaving together the alignments of old suburban railways with on-street trams through the city centre.

The Elizabeth Line is the most recent example: on its own it added 1.5 million, or 30 percent, to London’s labour market catchment – the people who can reach one of London’s three central business districts within 45 minutes by public transport. It has proved to be immensely popular: six of the ten busiest stations in the UK appear in a row in the Elizabeth Line’s core.

The total length of the Elizabeth Line is around 118 kilometres, but 100 kilometres of that existed already. Yet ridership still rose by about 300 per cent when it opened. In other words, London got three quarters of the ridership of a whole new branched metro line while having to build only one sixth of its length. This pattern is why crossrails have so persistently been a good investment around the world.

Compared to the major cities of the continent or Japan, however, Britain’s crossrailing efforts have been modest. London has crossrailed perhaps a fifth of its Victorian railway system, whereas Paris, Madrid and Tokyo have joined up nearly all of their terminating legacy lines. Huge swathes of South London, along with most of the great cities of the Midlands and the North, rely exclusively on the railways of the 1800s, low-frequency services terminating at overcrowded stations like Waterloo and Liverpool Street. Manchester has dozens of stations, but no capacity in the city centre to run frequent trains from these stations. The scope for further crossrails remains immense.

Funding through value capture

There are three main ways to fund rail infrastructure: taxpayer subsidy; borrowing against future fares; and value capture (both private and public). Wednesday’s de facto cancellation of the Leeds tram, to which the government had committed £2.5 billion, is a reminder of how risky it is depending on government subsidy in today’s fiscal constraints. Fare income funded the construction of most of Britain’s railways in the nineteenth century, but modern urban rail is both heavily price controlled and faces tougher competition than Victorian railways did, from aeroplanes and cars.

The remaining opportunity is value capture. When a railway service is improved, properties around its stations become more valuable because of their greater access to jobs and amenities. ‘Value capture’ means using some of that uplift to cover the cost of the improvements.

Value capture was widely used as a means of funding railways in the USA and Canada in the nineteenth century, and it was used in England to help fund the famous Metropolitan Line Extension into ‘Metro-Land’ in the early twentieth century. It has remained routine in Japan down to the present day. The recent Northern Line Extension was funded largely through value capture. Value capture has been used to fund crossrails in Paris, Hong Kong, and Tokyo, as well as about one third of the Elizabeth Line.

There are three main ways to do it. The first is speculation. A private or public corporation buys land near where a station is going to go, at near-farmland prices. When the railway is built, they sell or rent that land out. This is what Japan’s private railways and Hong Kong’s municipal railway operator do. It is how the Kansas Pacific Railroad was funded in the US, along with many streetcar suburbs.

The second is tax. With the tax model, a public authority, usually a local government, taxes some fraction of the value that the new infrastructure generates for property and landowners. Sometimes this is passive: countries like Switzerland, France, Denmark, the US and Japan with high taxes on property automatically get back some of the money they spend on infrastructure when it drives up home values. In other cases it is more active. Business improvement districts often approve new taxes on commercial landlords to fund investments that boost all of their revenues. American local voters often vote by referendum for their local authority to issue billions of dollars of bonds to build infrastructure like roads, repaid by increased property taxes.

The third is permissions. Many countries keep the permission to build homes scarce. In these countries, being granted permission to develop farm or industrial land into residential properties immediately raises the value of the land dramatically. The Resolution Foundation estimates that giving a landowner permission to build homes on London greenfield adds about £35 million of value per hectare. Charging for permission, or extra permission, to build around infrastructure is another standard way to fund it. Brazil’s CEPACs are a kind of auctioned development certificate that have raised billions for infrastructure in this way.

Since the government already wishes to give out extra permission, this third option is perfect.

A worked example

Here is one concrete example. The Great Northern line runs through the Hertfordshire green belt into Moorgate Station. Moorgate Station is small and currently achieves only eight trains per hour in the peak, although the tracks could take twenty-four. Meanwhile in South London the Sutton Loop line is limited to a train every half an hour in each direction, which contributes to the overloading of the Northern Line.

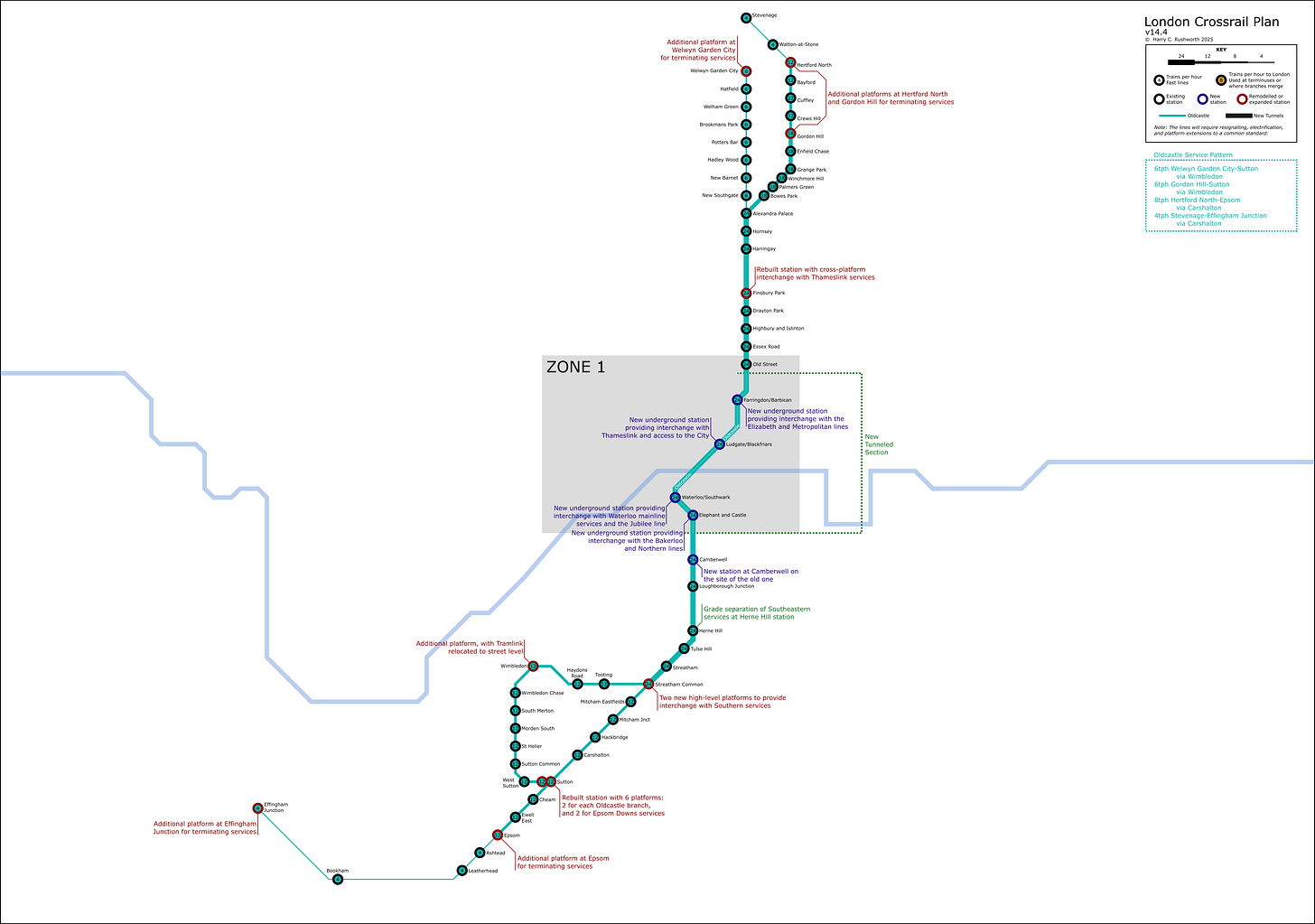

We propose constructing a new tunnel between the lines at Old Street and Elephant and Castle to join these two lines up. With some targeted infrastructure improvements including grade separation at Herne Hill and additional platforms for terminating, this route could be segregated from other services, allowing up to 24 trains per hour through the new core under central London, the same peak-time service as the Elizabeth line. We might call this the ‘Oldcastle Line’ as a portmanteau of ‘Old Street’ and ‘Elephant and Castle’, taking our lead from the Bakerloo Line.

The Oldcastle Line would roughly triple frequency on the Great Northern line north of Moorgate as well as sextuple frequencies at stations like St Helier in south London. It would also provide passengers from these stops with direct services to the City and the Southbank, and to direct interconnections with nearly every Underground line. Like the Elizabeth Line, the Oldcastle Line would be transferred to Transport for London.

In the north, the Oldcastle Line would take over a string of green belt stations, which would suddenly receive frequent and highly interconnected services into the capital. Many have abundant developable land under the Government’s new planning policies.

Consider Bayford, a small village with its own railway station on the GNR. Bayford Station has nearly 200 hectares of farmland within one kilometre’s walk. Granting it planning permission for 50 dwellings per hectare, as the government is intending, will give each landowner an immediate uplift of £35 million for each hectare they have, for a gross development value of £7 billion. We have identified ten stations like this on the Oldcastle Line alone. Many other lines are similar.

Working with a team of specialists, we are working on a plan for connecting suburban railways across Britain in this way, funded by the proceeds of a hypothecated charge on new planning permissions granted near stations. There are many engineering challenges, but they are surmountable.

The government need not accept our exact proposals. The important thing is that they accept the principle. Mass housing development without infrastructure will cause gridlock and backlash. Building infrastructure in arrears, when the taxpayer can be convinced to fund it, is foolhardy. Instead, the enormous uplift that will be generated by handing out millions of homes’ worth of planning permissions should be turned to providing the infrastructure they will require. In practice, doing that means development charges, hypothecated to new Crossrails.

The future of British urban rail

The 1930s remains the most prolific decade for housing delivery in British history in percentage terms, peaking in 1936 at nearly three percent of stock. Today that would be equivalent to 760,000 new homes built in a year, enough to achieve the Government’s target in just two years.

Doing this required a truly gigantic amount of new infrastructure. Under Sir Herbert Walker, the Southern Railway electrified hundreds of miles of track into Surrey and Sussex, creating the modern commuter belt. The Central, Northern, and Piccadilly, District were extended, connecting vast new suburbs to London and giving millions of Outer London swift connections to jobs and amenities.

The Ministry of Transport pushed through a massive program of arterial roads and bypasses, funded by the new tax on petrol, to unclog Victorian streets. This included the A40 Western Avenue, the A12 Eastern Avenue, and the North Circular (A406). A vast fleet of motorbuses and coaches created new transport connections across England.

Homes and infrastructure go together naturally. The Government’s schemes could deliver enormous numbers of homes. Land value capture would give us the infrastructure those homes need.

Section 106 (basically bargains between the developer and local planning authority to provide public goods), Section 278 (the same, but with the highways authority), and CIL (Community Infrastructure Levy, a cash payment system to local government mitigate the impacts of development)

I have believed for decades that London and our other major cities should always have a significant infrastructure project under construction. Finish one, commence the next. With this country’s intellectual and material resources - not to mention the proven financial benefits - this should be self-evident, but the Treasury doesn’t understand capital investment, and our politicians can’t countenance anything that doesn’t deliver results within a single parliament. Oldcastle would make an excellent Crossrail 3 - after the “Chelney” is under way.

Crossrail 2?