Why induced demand is fake

And roads are a pretty good way of creating agglomeration, actually

Here’s a post fleshing out some of the ideas I advanced in a recent Twitter thread. Basically I defend three ideas: first, Induced demand is not a useful idea. Second, infrastructure, including roads, is good, even if we become dependent on it. Third, transport (and the infrastructure that enables it) is a crucial way we get agglomeration, and roads are one good way of generating it. Roads are good, even though they have substantial downsides.

Induced demand is not a useful concept – the demand is always there, latent

There is a popular idea that if you build extra road infrastructure, it will just be filled up with new traffic, and thus, this extra roadspace hasn’t done anything to relieve traffic congestion. This theory is known as ‘induced demand’. Strictly, it is false, and we shouldn’t let it stop us building more roads, as doing so would make us richer and happier. However, this doesn’t mean more roadspace is good in every location. In fact, there are many places, like residential streets and city centres, which may have too much driving.

In a sense, the claims behind induced demand are true: in many cities there is such latent demand for driving that building extra road infrastructure – and charging nothing to those who wish to use it – will lead to no reduction in congestion.

Famously, RJ Smeed predicted in 1949 that London’s average road speeds would always be roughly 9mph, which they remained at for seventy years after this prediction. Any slower, and people took the tube, cycled, walked, or stayed at home; any faster, and more drivers flooded onto the road until it came back down.

But in another more important sense it is not true: more roadspace means more journeys. Even if the road looks just as congested, four congested lanes are carrying more people to their desired destinations than three or two congested lanes. One study of widening the M25 found that journey times worsened over the same period. But even in this study, the road let over 10% more people through the relevant junctions. (In fact, roads in general were seeing worsening times, and M25 speeds would likely have worsened more if not for the expansion.)

The demand is not really ‘induced’: it’s more true to say that it was always there – when the roads don’t exist to accommodate it you could call it ‘suppressed demand’. If we offer more subsidised social housing, more people tend to live in it – would we then say that demand for social housing has been ‘induced’?

Imagine a city with acute food shortages and controlled prices (e.g. Caracas, Pyongyang). People join long queues before bakeries daily, and still only average half their calorie needs. The supply of bread then improves so that they average 60% of their calorie needs instead. Would we really expect the queues to wither away? Of course not. They might not even get discernibly shorter. Does this mean that demand for bread is in some peculiar and distinctive sense ‘induced’? Of course not. Does it mean that going from 50% to 60% of calorie needs is not an improvement? Again, of course not.

More and better infrastructure lets us spread out and enjoy more space

A sophisticated version of the induced demand story says that as well as driving more on a better road network, people faced with a better road network, over time, shift towards living more car-dependent lifestyles. This is true. When infrastructure is reliable, people begin to depend on it. As a train commuter, I live a train-dependent lifestyle and when Southeastern trains (currently run by the Department for Transport) recently reduced the frequency at my station by 2tph I was incensed. If the trains had never existed, I would never have moved to Zone 3.

When our best mode of transport was walking, cities had a maximum size. Once things got more than a few miles – an hour’s walk – wide, it was beyond the distance where agglomeration was possible. So if there were sufficiently big advantages to the city – as in Ancient Rome, medieval Constantinople and Paris, or Georgian London – people built apartment buildings up and squeezed more and more people into the existing space.

Life was horribly overcrowded. In 1910, the densest tract of New York had around 150,000 people per square kilometer. Overall Victorian Manhattan had about 60,000 people per square kilometer across the city – as densely packed as its densest district today, and higher than famously crammed Dhaka today.

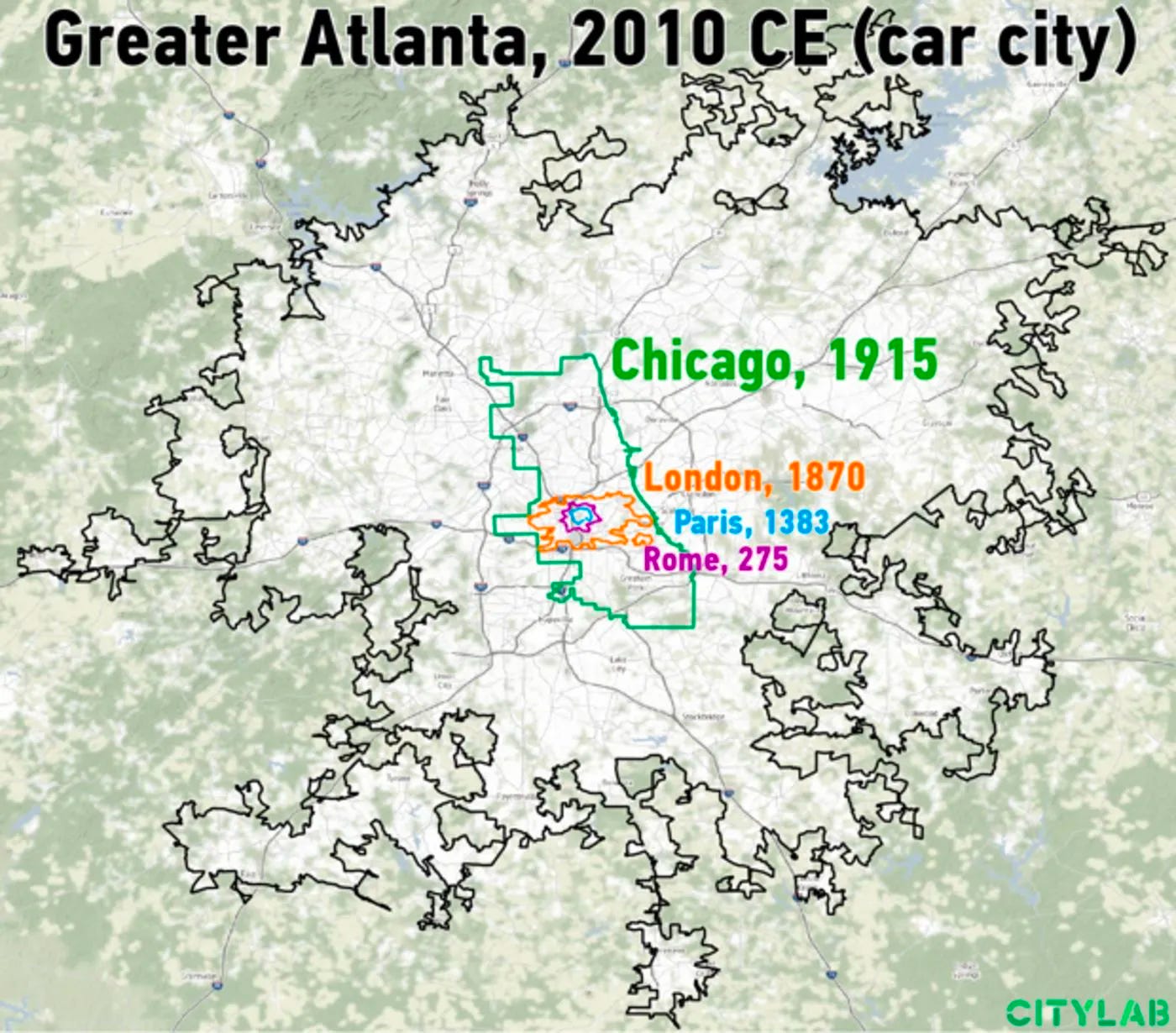

This was all lifted with infrastructure like the horse-drawn omnibus, and commuter train lines (Greenwich to London Bridge was London’s first – the world’s Dublin to Kingstown). And, yes, the car. Because cars can take you point to point and go anywhere you like, they are much more land-hungry than transit, but they also open up much more land for useful development. If you look at Atlanta on a satellite map it barely looks like developed land at all, but instead like a gigantic partly-inhabited forest – it has essentially achieved the goals of the Garden Cities Movement of Ebenezer Howard.

If house prices are above construction costs, that means that developers could profitably build, but they’re not being allowed, and it is a strong indicator that there is an undersupply of housing. In eighty percent of American cities, house prices are roughly equal to construction costs, suggesting that housing is relatively abundant. This in turn means it is generally affordable in these places to get married and have children. They also tend to have low homelessness. And in all of these places, it is because the city makes it easy to build outwards in all four directions.

People like space, and although things like crime push people to spread out more than is efficient, even in near-zero-crime societies with tolled highways and expensive parking like Japan, nearly everyone wants to own a car, and likes to spread out into quiet suburbs if they can.

So, yes, if roads exist, people plan their lives around them and use them more. But they do this with every technology. This is just how demand works – it’s not a special type of ‘induced’ demand.

So induced demand is not a helpful concept. We use roads because we want to get around, which we want whether or not roads exist. The upshot is that road infrastructure is good. Overall, for example, the US interstate highways are responsible for about four percent of US GDP.

The UK’s decision in the 1700s to allow private organisations to take over 11,000 miles of roads, charge tolls, and use the money for improvements, which led to ‘turnpike mania’, increased average road speeds from 2.6mph to 6.2mph. It, along with the canal boom at the same time, was surely an important ingredient into the industrial revolution.

Transport is very important, and roads can provide a lot of it

When we get in our cars to go somewhere, it’s because we value doing so – because we can go to work, to pick up something we need, meet a friend, or visit a family member. Roads are also an essential way we transport goods around and get emergency services where they are needed. We have an enormous latent demand for trips, and the more infrastructure we build, the more trips we do.

On top of the value you get from the roads you actually drive on, there is a bonus value to having infrastructure out there that you could use. You don’t know whether you will want to visit an Ethiopian restaurant, or get job on a specific side of town, regularly, or even ever, but you will likely still value this option.

Infrastructure owners, such as airports, can profit from this. But even if we do have tolls or road pricing it’s hard for those running the roads to charge you prices that fully reflect this benefit you get, since they can only charge you for the trips you do take, which means that the value these options create is usually ‘captured’ not by infrastructure operators, but by house prices, because people pay more to live near infrastructure which offers lots of potential.

Airports show this very clearly. You will take only a tiny infinitesimal fraction of the potential flights you could take from your nearest airport. But each year you enjoy having the option of taking them, since you don’t know where you might want to travel in future. Thus, airlines and airports capture only a tiny fraction of the value they create, and instead of paying airlines people pay to live nearby airports.

Living near Heathrow gives you many more options than living near Stansted, and living near Stansted is worlds apart from living near a small regional airport. If you are not in the flight path, every 1% further you get away from a major airport reduces your house price 0.15%.

The same is true for the road network. Roads increase the pool of jobs workers can get to in a given time – or on the flipside, the pool of employees a given employer can hire. A larger labour market means higher productivity. Homes with access to these higher productivity jobs are worth more. One Norwegian highway linking up villages in the South raised prices 5% across the region. Every mile closer homes were to a pair of toll road networks in Orange County in the 1980s was worth thousands of dollars in home value. And so on.

Sufficient road infrastructure can even allow what we might cheekily call a ‘15 minute city’ – pick anywhere in Lubbock, Texas and any other place and see how you can drive between those two places in 15 minutes.

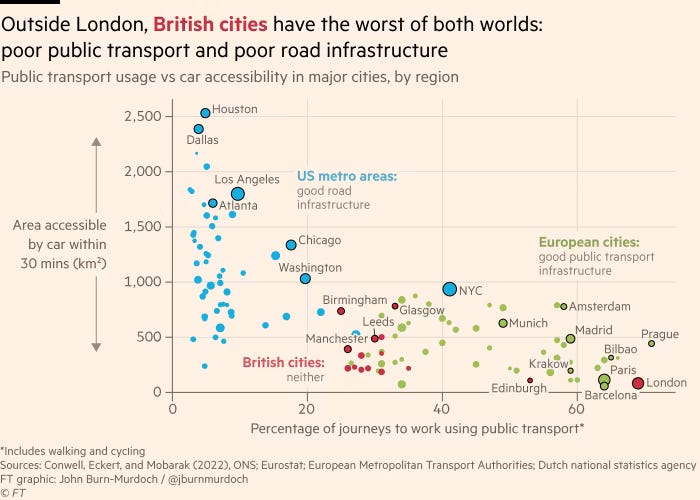

Although American cities – with more roads than nearly anywhere else – should have the worst congestion, through induced demand, they actually enjoy large agglomeration benefits, and allow people to get around pretty well. It would almost definitely be more efficient to provide a little less road infrastructure in some cities, and a little more transit, and to use congestion charges as well, to relieve peak time traffic, but the system’s success proves it basically works.

All of this doesn’t mean that we should bulldoze the best parts of our cities to build roads, as London attempted in the 1970s. Car traffic is noisy, it pollutes, it’s space-hungry, and it can be dangerous. This means that we may end up favouring things like low-traffic neighbourhoods and pedestrianisation – in the right places. We may also favour tolls or congestion charges. But equally, we should not use flawed arguments to try and pretend that roads are not an important form of transport that support our prosperity.

In the UK, our roads are horribly congested, and compared to competitors – such as for example France – we have many fewer and worse quality ones. Building them is insanely expensive, in part due to mistakes we have made around judicial review. We should do something about this.

Agree with the overall points, but I think many who use the term induced demand actually just mean suppressed demand. You are right that suppressed demand is a more accurate way of phrasing it.

Hot stuff here, very nice. Admittedly, I am less motivated to comment just to say "I agree" vs when I think there's an "umm,, akshually" point to be made, and I think there are maybe a few

- The Lubbock 15 min city, even if facetious, kinda misses one of the understated appeals of a "15 minute city" in that people should not *need* a car (with surprisingly large ongoing costs) to be able to get around normally and live a middle class existence

-- and, at least where I'm at, much of suburbia does have a "viable" density for transit eg every 15 min, 10 min (heck, even after the "streetcar suburb" era), and it is more authorities not budgeting or servicing it. Ie trying to think of it as meeting demand, like seeing if a bridge should be built by counting the number of people coming across (rather than considering suppressed demand)

- The "Atlanta is a Garden City" is a spicy take that feels kinda wrong, but I can't fault except for "the vibe" I guess all I can think of is the "forest" that Atlanta appears to be nestled in is really just suburbs. But, eh, a bunch of leafy suburbs is close enough? to a forest?

- And about the size comparison of Atlanta to Chicago - was Chicago in 1915 really confined to Cook County? I wonder if there were suburbs outside the county boundary that are still functionally suburbs of Chicago (like today, where suburbanisation? urbanisation extends over to Wisconsin and Indiana bythe looks of it)

Insightful to me