The nuclear taskforce's secret weapon

The one reform I'd wave through with a magic wand

The UK’s Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce, set up by Keir Starmer’s beleaguered Labour government nine months ago, headed by august regulator John Fingleton, and staffed by three top nuclear experts and an elite planning lawyer, has delivered its final report. For my money, it is as good a government report as you could reasonably expect, and if the UK implemented its reforms, we would instantly shift to being as well regulated as Czechia, France, and Finland, having been in a league of our own for poor nuclear governance.

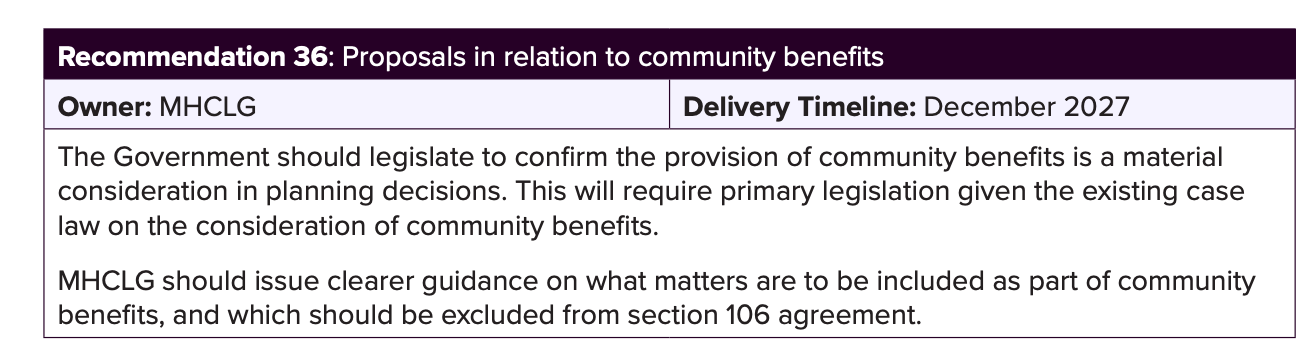

We should implement the sweeping and radical reforms to planning, environment and habitats protections, and radiological rules that the taskforce proposes. But if I had the power to push through one, and only one, recommendation from the list it would be Recommendation 36: Proposals in relation to community benefits.

The UK planning system is built around the principle that planners around the country are deciding on the socially optimal outcome, without reference to anyone’s individual interests. Everyone knows that planning is driven by democratic preferences in practice, but there is a widespread social myth to go with the law. A Victorian would have objected to new houses because they affected his view, or brought in social undesirables to the area. A modern Briton is obliged to pretend that he has some broader social purpose, like protecting newts, or maintaining the character of the area, or preventing excess nutrient runoff in the water.

This has been backed up by case law. In 1981, a local area was not allowed to impose the condition that a hangar was packed up after ten years on the grounds that if it was objectively good for the human race that the hangar be built, it couldn’t also be good to remove it after ten years. In 2019, a prospective wind farm developer offered four percent of the turbines’ receipts to local residents in exchange for allowing them to be built. The local community and its representatives said yes. Lord Sales ruled that planning permission ‘cannot be bought or sold’.

Development is allowed to mitigate harms, whatever the cost. So, for example, you can spend £700 million on preventing the deaths of 10 or 20 protected fish every year or two, or £120 million saving 300 somewhat rare bats. You can prevent every new building in London over building safety, or an appreciable fraction every new greenfield house in the country over alleged nutrient runoff.

Decisions like this create obvious perverse incentives. If councils are allowed to block development, so long as they can come up with some nice fluffy-sounding objection, like heritage, nature, or the environment, and their voters have every incentive to block it, because all development is obliged to benefit society as a whole but never the local community, then they will always find a way. Which is why I have said before that infrastructure costs are high in the UK because people want them to be high.

This change is the most radical in the report, and would fundamentally upend the whole purpose of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, and its associated reforms, which was to replace local government incentives for development with rational scientific planning. The TCPA’s problem was not that it gave local governments extra planning powers, though it did do that, but that it deliberately removed all the incentives local governments had to approve housing, and other development. This would reverse that, albeit only for nuclear power projects.

Once locals have an incentive to see development go ahead, whether that is housing or nuclear power, their position on bat tunnels, fish discos, pointless radiological interventions and so on changes dramatically. Suddenly they prefer development over delay and proportionality over uncontrolled cost. Evidence around the world shows this.

Hundreds of thousands of homes in Seoul were built through joint redevelopment projects, a kind of land readjustment where Korean shantytown dwellers could vote by supermajority to upzone their neighbourhood to 55 storeys. Senakw, is a project in Vancouver where the local Squamish nation voted to upzone their own land outside the city centre to similarly huge towers. When asked whether they would impose a swathe of environmental, nature, and other cost-increasing bylaws that they happened, as a First Nation, to be exempted from, a spokesperson said ‘we have decided to maximise economic benefits for the community’, or in other words, ‘no’.

Israeli apartment dwellers, who now have the power to agree by supermajority to demolish their building and put a bigger one on its site, now often sue their local government to be more permissive. Houston, USA’s permissiveness is backed up by a community right to opt out of reforms.

Most importantly, the gigantic French buildout of nuclear power was enabled by extreme generosity to locals. ‘Avoine, the commune that hosted the first EDF reactors, for example, saw annual revenue jump from tens of thousands of francs in the mid 1950s up to nine million a year by the time EDF2 and EDF3 were being brought online in 1964–1966. Locals dubbed their town “the Kuwait of Indre-et-Loire”…The northeastern town of Chooz has offered its residents free high-speed internet and a 120-channel TV subscription since 1999. In 2012, local councils in France paid an average of €35 in subsidies or benefits per local resident. In the 19 areas that hosted nuclear power, the average was €450.’

No wonder France had such a weak anti-nuclear movement. Most of the people who might have campaigned against it – angry locals – were neutralised. And no wonder that France is having trouble with its latest wave of nuclear power, as it is shifting substantially away from local taxes towards nationalisation.

It would take a while for this change to bed in. Therefore, I think the ideal option for the government is to simply take the flak and implement the report in full. Eventually the local benefits may make the equation work. But if I could get only one reform from the report it would be this one, which could fundamentally change the public’s view. The public is softly pro nuclear power, but with little sense of the upside of fixing regulation. By giving them a direct stake, this could change that, and while it’s doing so, create a case for changing the planning system across the board.