How to think about immigration and housing

Since Brits own Britain, more demand for Britain is generally good for us

One concern about immigration to the UK is that since housing supply is very restrictive, it harms natives via intensifying competition over the existing stock. A better model to use is that immigration drives up the value of housing permits. To the extent it harms Brits that want more housing it benefits those that own their own home or are landlords. But it also stores up extra value in permits that Britain can access at any time it chooses.

The simple supply and demand story about immigration and the housing market is appealing, intuitive, and broadly right. More immigrants in the UK means more demand for housing in the cities where those immigrants intend to live. Because the supply of housing in the UK is extremely ‘inelastic’ – it doesn’t respond to increased demand due to restrictions on development – this drives up house prices and rents. One government paper put this impact overall at 20% from 1991 to 2016. Since prices rose about 300% above inflation during that period, that would be a relatively small fraction of the overall rise.

Scarce housing has all sorts of problems. But most of these happen through deterring migrants (internal and international) from coming to the city, so too many people coming can’t be a cause of these knock-on problems like innovation (of course it can still be bad for the natives who face more expensive housing!)

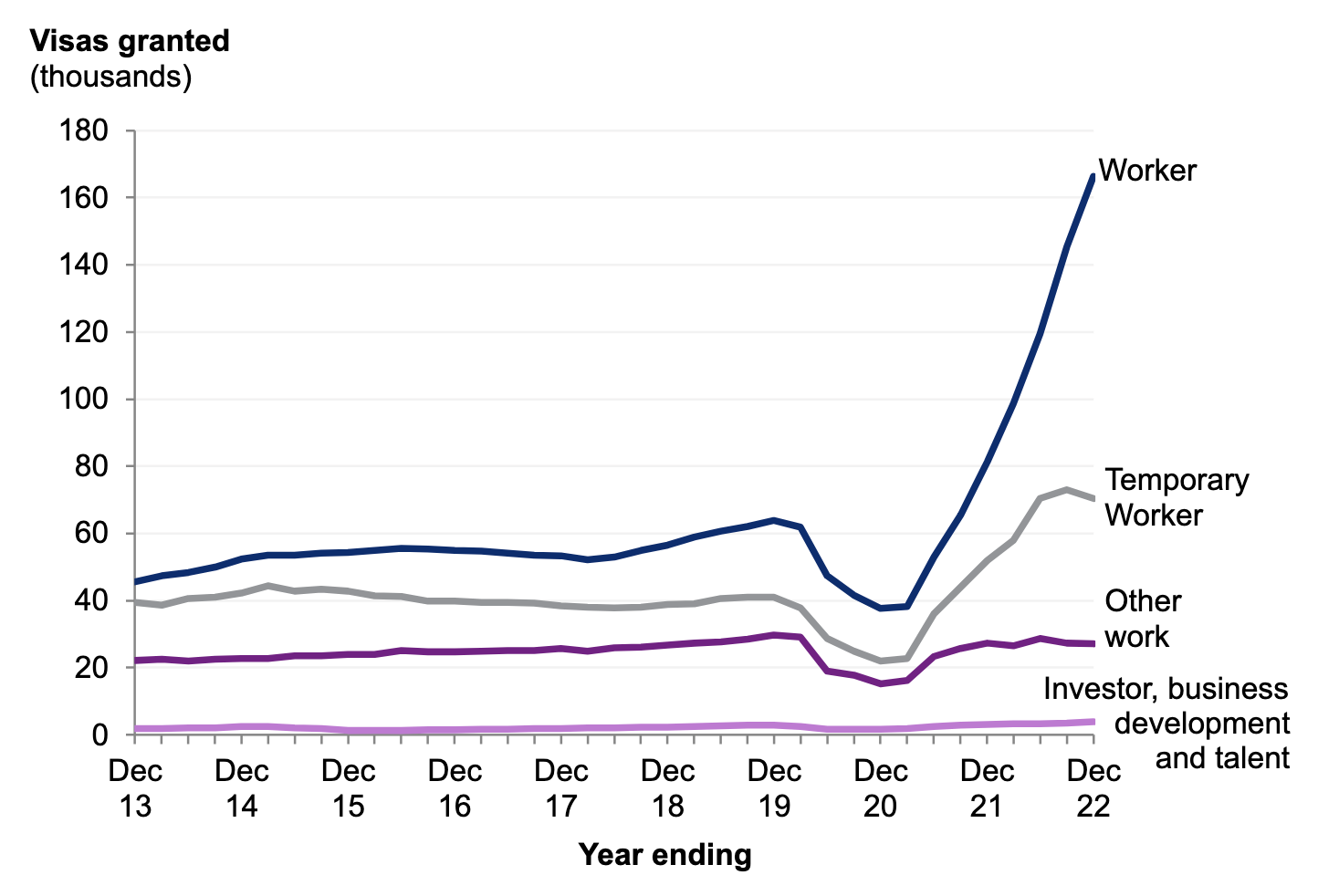

Recently, the UK has had a wave of over one million migrants coming in during one year (about five times the rate seen in the USA right now, close to the rates seen in Australia and Canada). Seemingly this rise above previous levels has been driven in part by pent-up student demand from the Covid years, in part by refugees from the Ukraine war and China’s takeover of Hong Kong, and in part by generous rules on NHS and social care workers.

This rapid spike in immigration may be the key reason why not only has there been a rapid worsening in the UK’s urban rental markets with many lurid stories of huge queues at viewings and massive over-asking-price offers, but that this has spread beyond the usual hotspots of Cambridge, Oxford, and London. Cities like Glasgow with important universities, and which have typically faced very low property prices by UK standards, have seen rents spike – one wealthy American student was apparently forced to buy a flat as rental property was so scarce.

How does higher demand for housing affect Britons? Around two-thirds of the country owns their own home. There are also 4.4m landlords, and 95% of these are British. For two-thirds of the country, plus the landlording six percent, this higher demand is mostly good, unless they are eager to upsize. For the other third, it is probably bad. It is definitely bad for private tenants, who face higher rents (they lose to the same extent landlords win). Social tenants generally have very secure tenancy, meaning existing tenants may not be heavily affected. But for those prospective social tenants who miss out on a flat or house due to an incoming immigrant taking their place it is pretty bad: as well as being secure, social housing is very heavily subsidised.

So two thirds of the population win, and one third lose. But how exactly does this happen?

Increased demand for housing leads to appreciating land values. But it is not really the land which increases in value, or even the structures on top of the land, but the permissions that allow farmland, worth a mere few thousand pounds per acre, to become developed land, worth millions per acre. Or, to say the same thing, allow low density developed land to become moderate or high density developed land.

So we drive up the value of these permissions by allowing many more people into our country without releasing more land for development. But the great thing is that these permissions don’t cost us anything to provide. We are effectively storing up value that careful housing policy could release.

The more high-skilled, positive-externality-rich immigration the more, for example, the planning permission associated with a community land auction is worth. Giving planning permission to a single 10 or 20 acre field near a suburban station might be worth tens of millions of pounds for an affected local area, which runs to a lot of potholes, council tax reductions, bus services, and new trees. This would be, in effect, a transfer from the migrants (and other renters) to the local community (likely shared with the landowner, developer, and national government, depending on how we release the money).

Of course, right now the planning system isn’t well set up for releasing this permit value. In fact, it never has been suited to doing this, as it is built around the idea that central planners should be able to tot up costs and benefits, make the socially optimal decision, and ride over political objections without needing to incentivise acceptance or compensate those who lose out. It flat out rejects win-win trades.

Once we release this permit value, all of the country should benefit, not least because we would also make housing and buildings – one of the most important factors of production – much more freely available.

Of course, you may well say that Britain has had 75 years of housing failure without changing anything or at any point building enough homes, the last time we did that was in a fundamentally different world, the 1930s. You would be right. But I have hope. We have only recently fully understood why the planning system fails to deliver enough homes, and come up with schemes, like community land auctions mentioned above, to capture the stored up permission value, and give it to the affected communities to unblock the system. These schemes are based on numerous success stories around the world, and are already influencing UK policy. It’s a matter of time.

Of course, if I am wrong, then the one third of society that is private renters, or those who would like to be social renters, but are blocked by a foreign tenant, can reasonably complain about losing out, though the other two-thirds who own land should be pleased. But as a whole, it’s good for UK plc if there’s more demand for the biggest asset we own: our land.

Good post, Ben. You say that "two thirds of the population win, and one third lose". But surely some of the people living in the 65% of households led by homeowners are people who can't afford to move out and live on their own?