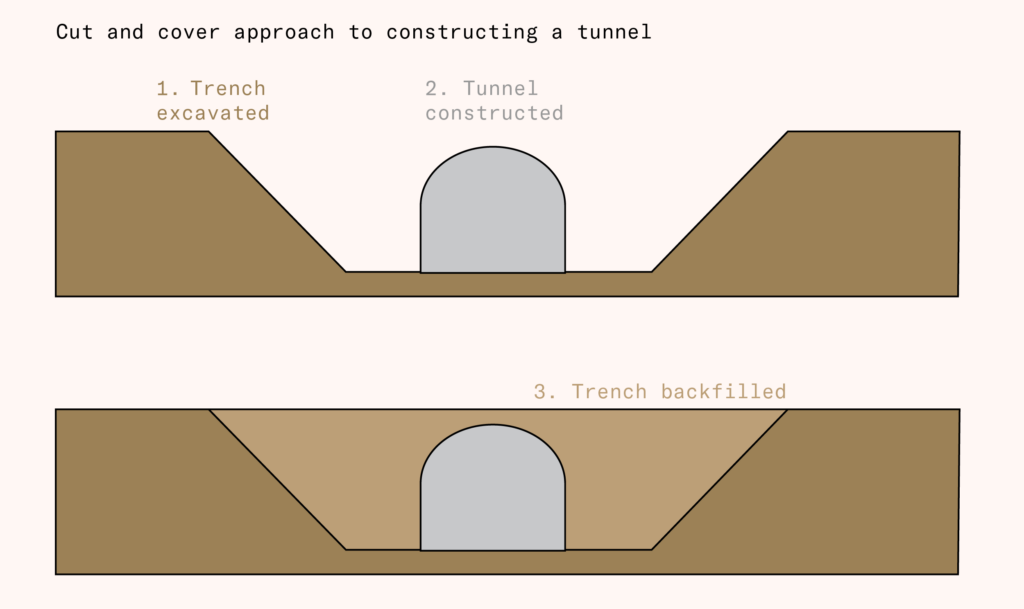

Brian Potter has a wonderful essay in the latest Works in Progress – Issue 14, which just came out in February – explaining why infrastructure is now usually built with tunnel-boring machines, rather than by digging a trench, building a tunnel structure, and then covering it back up.

In short: tunnel-boring machines got a lot better, and as people got wealthier they got a lot more sensitive about the huge disruption caused by building cut and cover.

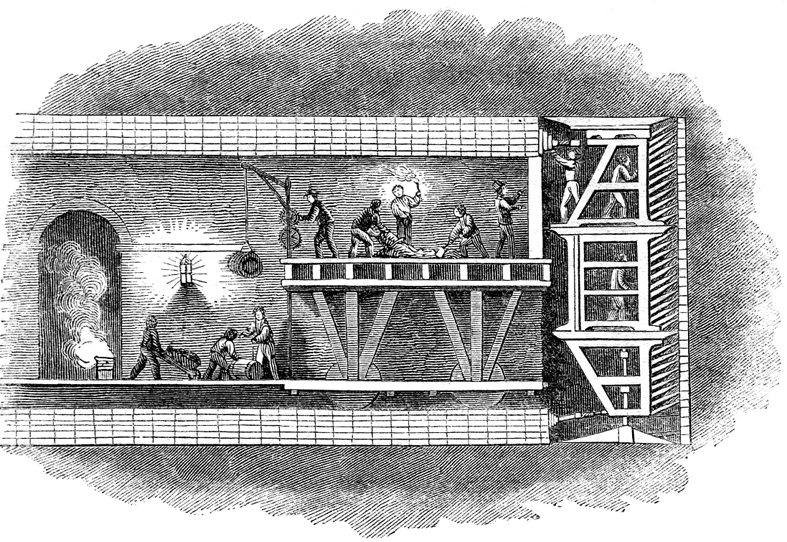

In typical Potter style you learn along the way how disc cutters were invented and work, and how fast Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s father Marc built his tunnel under the Thames at Rotherhithe (about eight feet per week).

I think Brian is right: building cut and cover has serious political issues that have not been addressed. However, I am a little more optimistic than he is that they could, theoretically, be addressed, partly by parallel to housing.

Europe and North America have both seen very little urban intensification since the second world war. Where cities have grown, it has been almost entirely through outward expansion – for example two thirds of Paris inside the peripherique is surviving fabric from before the second world war, and the population there has fallen from nearly three million to a little over two. But the broader built-up area has almost tripled in extent, and the metropolitan area has doubled in population. City population densities have fallen around the world. The heights of the tallest skyscrapers in the world have barely grown in the entire postwar period.

One conclusion to draw would be that building upwards is impossible due to our wealth and greater intolerance of the disruption such development causes. Sprawl is inevitable. But through changing institutions, people around the world have managed to make intensification acceptable to the public, or even popular.

Houston has added 80,000 townhomes on existing low density neighbourhoods. Washington, DC, has densified its metro stations. Israeli apartment owners have opted into demolishing their own properties and rebuilding them. New Zealand managed to upzone a significant fraction of the entire country by exempting the most precious historic neighbourhoods. Fifty-thousand accessory dwelling units have been added to California backyards, and ADU builders expect half a million more over the next ten years.

Vancouver’s Squamish people, a First Nation there, have been completely explicit about how they have been able to bring cost down substantially by junking burdens like affordable housing (they are able to avoid normal Vancouver bylaws if they wish), when 87 percent of them voted to add 6,000 apartments and 200,000 square feet of commercial space on 12 acres they own next to the center of Vancouver. They said the project was designed to ‘maximize economic benefits for the Squamish Community’.

Lots of the costs and complaints associated with modern development are cynical exploitations of institutions by groups that have been given vetos. If whole communities could choose for themselves (and keep the money saved) they would often choose a more cost-efficient and quicker option, even given its attendant costs. After all, HS2’s tunnels cost £700m per mile.

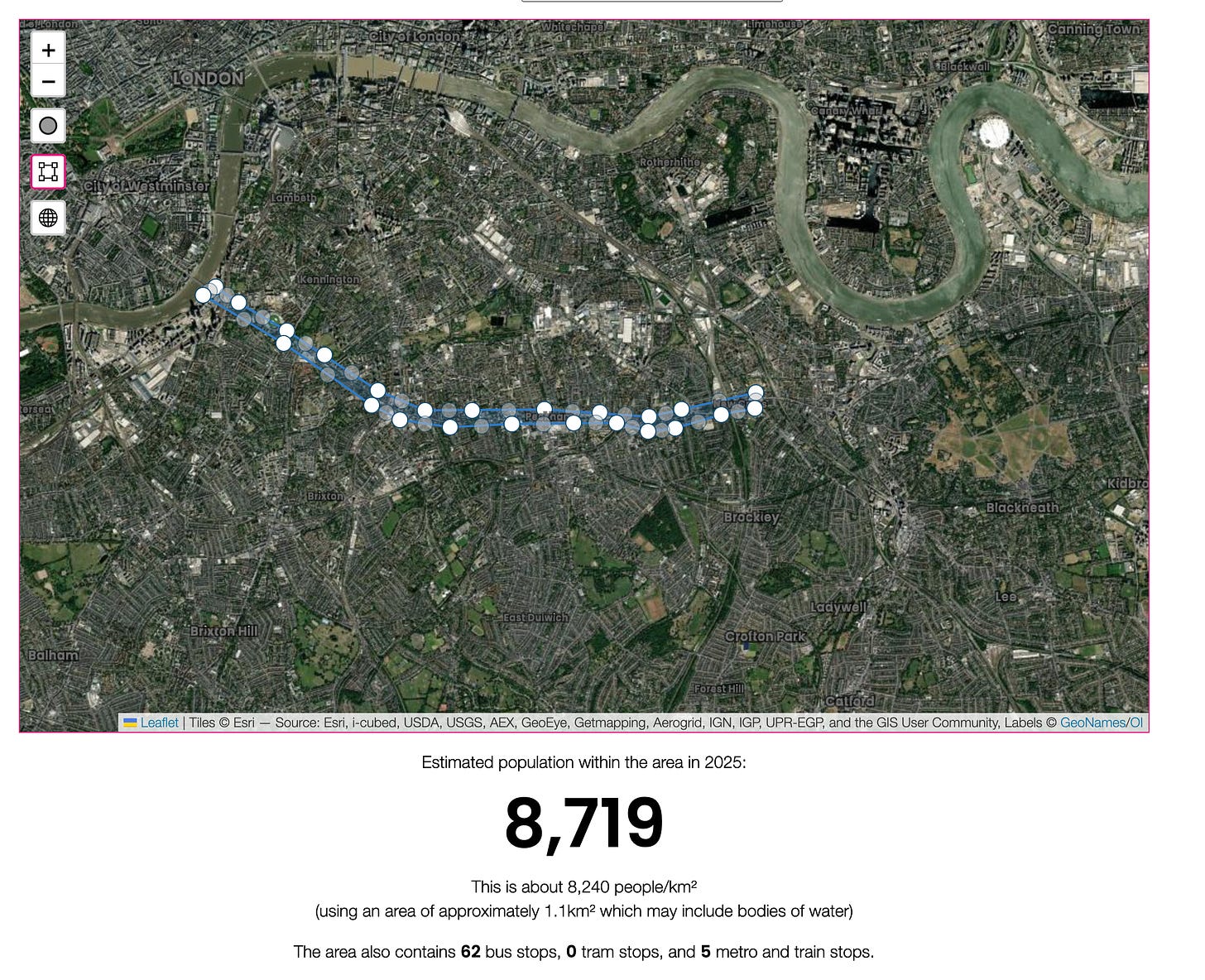

What would this institution look like? Choosing the exact thresholds is a bit of a lumping/splitting question – there is no perfect answer. For cutting and covering an urban road, I propose that the developers get majority (or perhaps supermajority) approval from residents living on that road, or living up to 50 metres away on any road feeding onto that road.

For cutting and covering the A2 between Vauxhall and New Cross, for example, that would mean asking about 9,000 people in the polygon above (created with Tom Forth’s wonderful tool).

Of course, these would not be the only people affected by closing such an important spine of South London. With current technology, it might be possible to identify and ask the other affected people – though perhaps automatic numberplate recognition systems could also tell us who drove the road regularly over the past three years, and we could get their approval too.

Such a system could have other benefits: it could be the starting point of an extra way to approve infrastructure, going directly to the voters. This is done widely for funding infrastructure. For example, American counties and cities often ask their voters to approve higher property taxes to guarantee bonds they issue – for billions of dollars – to build new roads, pipes or hospitals. This mechanism was exploited to its greatest extent in New Zealand, where such bonds built the Auckland Harbour Bridge.

Directly approving funding with the voters helps with approvals, because it’s inarguable that the public wants it to go ahead – it has a powerful mandate. It might be possible to take this even further and carve out much of the approvals process with direct public votes. If this did happen, then the mechanism could be a way around our infrastructure morass in general, even for projects that do not involve cut and cover or extreme local spillover costs.

Of course, I could be completely wrong, and tunnel-boring may have improved so much that cut and cover plus compensation is always more expensive. But the sample of projects is so small, messy, and distorted that I think we should find out first.